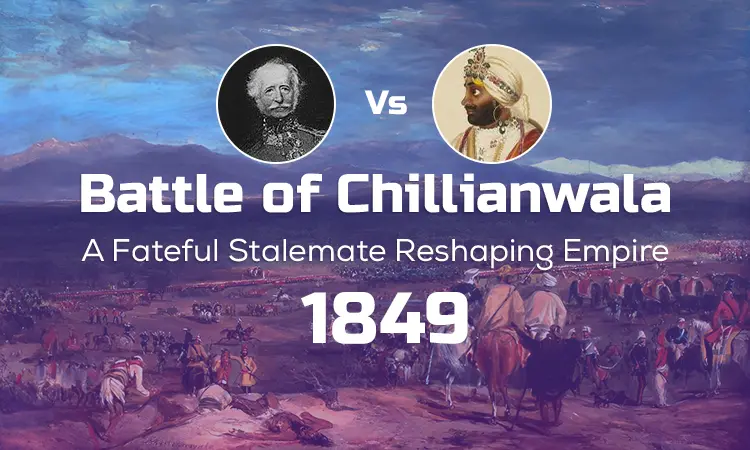

Clash at Chillianwala

In a fateful clash amidst the ancient lands of Chillianwala, the echoes of the Second Anglo-Sikh War reverberated in January 1849. Amidst the verdant landscapes of Punjab, the Battle of Chillianwala unfolded, etching its name in history as one of the bloodiest encounters witnessed by the British East India Company. When the smoke cleared, both armies stood their ground, their claims of victory echoing through the winds. Yet, this stalemate served as a resolute check to the immediate British ambitions in India, striking a blow to the very core of their military prestige.

| Event | Description |

|---|---|

| Battle Name | The Battle of Chillianwala |

| Date | 13 January 1849 |

| Location | Chillianwala, Punjab region |

| Opposing Forces | British Army under General Gough Sikh Army led by Sher Singh Attariwalla |

| Result | Both armies held their positions; Sikhs withdrew north |

| Testimony | "The Sikhs fought like devils, fierce and untamed... Such a mass of men I never set eyes on and as plucky as lions: they ran right on the bayonets and struck their assailants when they were transfixed." - British observer |

| Consequences | - British claimed victory due to Sikhs disengaging first - General Gough was relieved of command and replaced by General Charles James Napier - Battle of Chillianwala contributed to the Indian rebellion of 1857 - Sikh soldiers in British forces remained loyal and helped suppress the rebellion |

Prologue

In the Punjab, a land that had recently tasted the bitter fruit of loss to the British East India Company in the First Anglo-Sikh War, the flames of the Second Anglo-Sikh War ignited in April 1848. The seeds of rebellion took root when Dewan Mulraj led a revolt in the city of Multan. Frederick Currie, the East India Company's Commissioner for the Punjab, dispatched local forces to quell the uprising, among them Sikhs who once served in the renowned Sikh Khalsa Army, now under the leadership of Sher Singh Attariwalla. Alarmed, some junior British Political Officers witnessed this unfolding with wary eyes, aware of Sher Singh's father, Chattar Singh Attariwalla's seditious plans in Hazara, north of Punjab.

On that fateful day of September 14th, Sher Singh's army too raised their banners in defiance. Despite their shared opposition to the British, Mulraj and Sher Singh held no common aims. Determined to unite forces, Sher Singh embarked on a northern journey to join Chattar Singh, who had also rebelled. However, British officers had already taken strategic measures to secure vital fortresses. Chattar Singh found himself trapped in Hazara, unable to break free as the British held Attock, guarding the Indus River, and the passes through the Margalla Hills, which separated Hazara from Punjab. Meanwhile, Sher Singh advanced a few miles north, fortifying the crossings over the mighty Chenab River, awaiting the unfolding of events.

In response, the East India Company made their intentions clear—to depose the young Maharaja, Duleep Singh, annex Punjab, and seize the lands of any landholders who joined the rebellion. While Major General Whish's army resumed the Siege of Multan, the company commanded the formation of an Army of the Punjab under the experienced Commander in Chief, Sir Hugh Gough. Yet, both Gough and the youthful Lord Dalhousie, the Governor General at the tender age of 37, chose to delay operations until the monsoon season concluded. This unforeseen respite allowed Sher Singh to amass reinforcements and fortify his positions with unwavering resolve.

Finally, on that decisive day of November 21st, Gough assumed command of the Army. The following day, his forces launched an assault on Sher Singh's bridgehead at Ramnagar, situated on the left bank of the Chenab. However, their hopes were met with a resounding repulse, bolstering the spirits of the Sikh warriors. On December 1st, a courageous cavalry division under Major General Joseph Thackwell crossed the Chenab upstream from Ramnagar, drawing Sher Singh into a fierce day-long artillery duel at Sadullapur. As dusk descended, Sher Singh chose to retreat to the north, leaving behind echoes of a fierce struggle.

In the wake of the retreat, Gough halted, awaiting further instructions from Dalhousie. In early January 1849, news arrived—a mixed bag of triumph and trepidation. Multan had been recaptured by the British, although Mulraj still held the citadel. However, the Muslim garrison of Attock had defected to Amir Dost Mohammad Khan of Afghanistan, who offered half-hearted support to Chattar Singh. The fall of Attock did pave the way for Chattar Singh's forces to break free from Hazara and march southward. Swift and decisive, Dalhousie issued orders to Gough—seek out and obliterate Sher Singh's primary army before the Sikh forces could unite, disregarding the need for reinforcements from Multan.

And thus, the stage was set for a relentless pursuit, a dance of swords and strategy, as the Second Anglo-Sikh War unfolded its dramatic

The Beginning

As the sun cast its golden rays on 13th January, Gough's formidable army marched with purpose towards Rasul, the reported position of the Sikhs. Chillianwala fell under their control after a fierce clash with a Sikh outpost, setting the stage for the unfolding drama. Gough originally planned a calculated maneuver to attack the Sikh left flank the following day, but a vantage point near Chillianwala revealed a startling revelation—the Sikhs had advanced from their original positions along the ridges by the Jhelum River. Sher Singh, with his audacious move, foiled the British's intended flank attack, leaving them with no choice but to face the enemy head-on.

Estimates varied regarding the strength of Sher Singh's army. While some claimed 23,000 troops, including 5,000 irregular cavalry and 60 guns, others believed the numbers to be higher, exceeding 30,000. Regardless, the once-mighty Khalsa had been significantly diminished after the First Anglo-Sikh War, reducing their ranks to 12,000 infantry and 60 guns. Some historians argued that the Sikh army on that fateful day could not have surpassed 10,000 warriors.

The Sikh forces comprised three main bodies. Sher Singh commanded the left flank, stationed on low hills and ridges, with one cavalry regiment, nine infantry battalions, irregulars, and 20 guns. Lal Singh led the center, concealed within belts of scrub and jungle, boasting two cavalry regiments, ten infantry battalions, and 17 guns. Anchored on two villages, the right flank consisted of a brigade that had once guarded Bannu, comprising one cavalry regiment, four infantry battalions, and eleven guns. Sher Singh's left flank extended further with the presence of irregulars.

Intent on delaying the attack until the next day, Gough's plans were abruptly interrupted as hidden Sikh artillery unexpectedly unleashed its deadly fire from much closer positions than anticipated. While Gough later claimed concerns of an overnight bombardment, some officers suspected the sting of the Sikh's unexpected aggression had pushed him into swift action.

Gough's formidable army boasted two infantry divisions, each composed of two brigades, with each brigade consisting of one British and two Bengal Native infantry battalions. Accompanying them were 66 guns from the Bengal Artillery and Bengal Horse Artillery. Sir Colin Campbell commanded the 3rd Division, deployed on the left, supported by two field artillery batteries and three horse artillery troops. On the right, Major General Sir Walter Gilbert led the 2nd Division, accompanied by a field artillery battery and three horse artillery troops. Major General Joseph Thackwell's cavalry division was split, with one brigade positioned on each flank, Brigadier White's on the left and Brigadier Pope's on the right. Positioned in the center were two heavy artillery batteries, boasting eight 18-pounder guns and four 8-inch howitzers. In reserve, Brigadier Penney's brigade of Bengal Native troops stood ready.

And so, as the forces faced each other on the battlefield, destiny held its breath, waiting to unfold the tale of Chillianwala in all its valor and tragedy.

Here comes the Battle of Chillianwala

As the clock struck 3:00 pm, Gough's command echoed across the battlefield, signaling the commencement of the British advance. However, it was the right-hand brigade of Campbell's division, led by Brigadier Pennycuick, that encountered immediate challenges. The dense jungle hindered coordination, prompting Campbell to personally assume command of the left-hand brigade under Brigadier Hoggan. Pennycuick's troops, including the newly arrived 24th Foot regiment, pressed forward with great speed but struggled to maintain unity amidst the thick scrub. Their valiant attempt to confront the Sikh guns head-on proved costly as they fell victim to devastating grapeshot fire. The Sikh resistance was fierce, and the 24th Foot found themselves forced to retreat after reaching the heart of the Sikh positions. It was during this tumultuous struggle that the Queen's colors were lost, their fate remaining uncertain, either destroyed or perhaps buried with the officer who carried them. Pennycuick's brigade became disorganized, with small groups making their way back to the starting point. Tragically, Pennycuick himself fell in the line of duty.

In contrast, Campbell's left-hand brigade, led by Brigadier Hoggan, experienced greater success. The 61st Foot regiment captured several guns and even an elephant, while Brigadier White's cavalry delivered a decisive charge. Hoggan's troops eventually linked up with Brigadier Mountain's left-hand brigade from Gilbert's division, forming a formidable force behind the Sikh center positions.

Unfortunately, disaster struck on Gough's right flank. Although Gilbert's two brigades initially pushed back the Sikhs, capturing or rendering several guns useless, Brigadier Pope, plagued by illness, made a fateful decision. Ordering an ineffective cavalry charge through thorny scrub, confusion gripped his brigade, leading to a panicked retreat. The 14th Light Dragoons, one of the British cavalry regiments, fled in disarray, allowing the Sikhs to seize four guns. They then launched a rear attack on Gilbert's right-hand infantry brigade, commanded by Brigadier Godby, intensifying the pressure until Penney's reserve brigade came to their aid.

With darkness descending upon the battlefield, the Sikhs, though suffering heavy casualties, continued to valiantly resist. Recognizing the need to regroup and tend to his battered formations, Gough issued the order to withdraw to the starting line. While every effort was made to retrieve the wounded, some were lost amidst the dense scrub. Tragically, many abandoned wounded fell victim to roaming Sikh irregulars during the night. Gough's retreat allowed the Sikhs to reclaim all but twelve of the guns captured earlier in the day.

The Battle of Chillianwala had raged fiercely, with both sides displaying courage and determination. While the Sikhs faced immense challenges, their steadfast resistance left an indelible mark on the pages of history, showcasing their resilience and valor in the face of adversity.

Result

Gough's army suffered significant losses in the Battle of Chillianwala. The final tally included 757 soldiers killed, 1,651 wounded, and 104 missing, resulting in a total of 2,512 casualties. Remarkably, a considerable number of these casualties, nearly 1,000, were British soldiers rather than Indian troops. The devastating blow fell upon the 24th Foot regiment, which endured a staggering 590 casualties, accounting for over 50 percent of the total British losses.

On the Sikh side, casualties were estimated at 4,000 dead and wounded. The fierce engagement took a toll on both forces, with lives sacrificed on both ends.

In remembrance of the fallen, the British government later erected an obelisk at Chillianwala, bearing the names of those who lost their lives in the battle.

The Battle of Chillianwala concluded with both armies maintaining their positions, while Sher Singh's Sikh forces retreated to the north. Although both sides claimed victory, the British considered themselves triumphant as the Sikhs disengaged first. Nevertheless, the battle left a lasting impact on British morale and highlighted the fierce determination and martial prowess of the Sikh army. A British observer described the Sikhs as fighting like untamed devils, displaying incredible bravery by charging even when impaled on bayonets. Despite the British advantages in numbers, weather, and logistics, they failed to defeat their opponents at Chillianwala, leading to criticism of their commander, General Gough. The battle's outcome, coupled with other factors, contributed to the Indian rebellion of 1857. Notably, Sikh soldiers within the British forces remained loyal and played a vital role in suppressing the rebellion.